Focusing on Bronze Age People

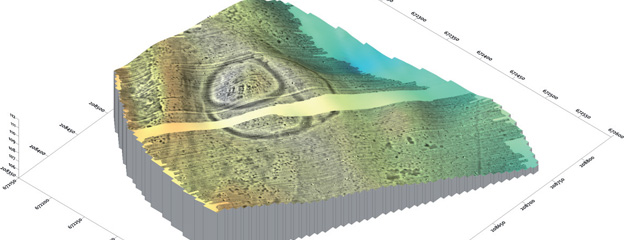

The ‘Momentum’ Mobility Research Group of the Institute of Archaeology, HAS RCH aims to get a better understanding of the lifestyle of Bronze Age people during a five-year period of research. The title of the programme ‘From bones, bronzes and sites to society: Multidisciplinary analysis of human mobility and social changes in Bronze Age (2500-1500 BC)’ also expresses this idea as, by examining human remains from burials, bronze artefacts and traces of settlements, we would like to create more detailed outlines about the diet, attire, tool making processes or ceremonial rituals throughout this thousand-year period.

Another important aspect of research is understanding human depictions of the era. Pieces of Scandinavian Rock Art are probably the most well-known examples of human representations of the era and perhaps they are the easiest to comprehend as they usually depict easily recognisable, sailing Bronze Age warriors equipped with swords or battle axes.

Rock carvings from Tanum and Askum, Sweden

(http://www.rockartscandinavia.com; Ling–Uhnér 2014)

Human depictions on clay or bronze artefacts are also known from the Bronze Age of Hungary. Some of them are easily understandable for the modern viewer such as the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1500 BC) urns from Mende–Leányvár or Százhalombatta–Földvár. On one of the vessels, an imitation of a bronze dagger refers to the male principle, while on the other, plastic knobs represent feminine attributes.

Clay pots symbolizing man and woman (after Sorensen–Rebay-Salisbury 2008, Fig. 6.)

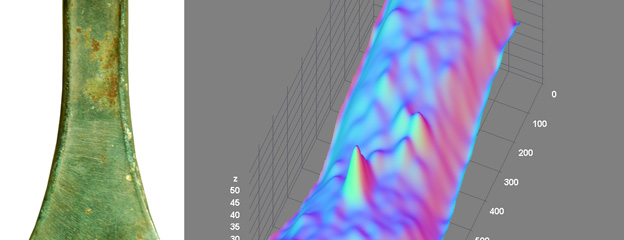

Other representations are so stylized that their understanding needs deeper analysis. For example, the plastic clay ribs on an urn from the end of the Early Bronze Age (around 2000 BC), excavated at Rákóczifalva–Kastély-domb are usually interpreted as a symbol of a human figure with raised hands. The same motif can be seen on a small mug from a contemporaneous grave from Szigetszentmiklós. ‘Comb figures’ (dress ornaments made of bronze) from Transdanubian graves or from the so-called Tolnanémedi type hoards can be dated to a little later. A mold from the settlement of Mucsi (Lengyel) – Sánc could have been used for casting bronze pendants like the one found at the eponymous site of the treasures.

Representation of a human figure with raised hands on Early Bronze Age grave pottery from a. Rákóczifalva – Kastélydomb, b. Szigetszentmiklós – Felső Ürge-hegyi-dűlő, Grave Nr. 139. (after Csányi 1992, Abb. 47; Patay 2009, 9. ábra), c. Middle Bronze Age dress ornament from Tolnanémedi and a stone mold of a similar object from Mucsi (Lengyel) – Sánc (after Bóna 1975, Abb. 22., Taf. 269. 10.)

The official logo of the ‘Momentum’ Mobility Research Group is based upon this latter pendant type that represents either the people or the characteristic bronze dress ornaments of the era. Instead of the typical five or six ‘comb feet’ we used three, each of them symbolizing one of the three ‘pillars’ and teams of our programme: (1) traditional and bioarchaeological examination of human remains from Bronze Age burials, (2) analysis of bronze tools, weapons and jewelry and (3) detailed investigation of houses and settlement structures with a special regard to understanding the constantly forming groups of contemporaneous society.

The logo of the HAS RCH IA ‘Momentum’ Mobility Research Group

Bibliography:

Bóna, I. 1975. Die mittlere Bronzezeit Ungarns und ihre südöstlichen Beziehungen. Archaeologia Hungarica 49. Budapest.

Csányi, M. 1992. Bestattungen, Kult und sakrale Symbole der Nagyrév-Kultur. In: Meier-Arendt, W. (Hrsg.): Bronzezeit in Ungarn. Forschungen in Tell-Siedlungen an Donau und Theiss. Frankfurt am Main, 83–88.

Keszi T. 2015. Pont, pont, vesszőcske – hová lett a fejecske? Magyar Régészet 2015 tél.

Kiss, V. 2009. The Life Cycle of Middle Bronze Age Bronze Artefacts from the Western Part of the Carpathian Basin. In: Kienlin, T.–Roberts, B. (eds): Metals and Societies. Studies in Honour of Barbara S. Ottaway. Universitätsforschungen zur Prähistorischen Archäologie 169. Bonn, 328–335.

Kovács, T. 1992. Glaubenswelt und Kunst. In: Meier-Arendt, W. (Hrsg.): Bronzezeit in Ungarn. Forschungen in Tell-Siedlungen an Donau und Theiss. Frankfurt am Main, 76–82.

Ling, J.–Uhnér, C. 2014. Rock art and metal trade. Adoranten 21 (2014) 23–43.

Patay R. 2009. A Nagyrév-kultúra korai időszakának sírjai Szigetszentmiklósról – Burials of the early Nagyrév culture from Szigetszentmiklós. Tisicum. A Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Megyei Múzeumok Évkönyve 19 (2009) 109–227.

Poroszlai 1992. Százhalombatta-Földvár. In: Meier-Arendt, W. (Hrsg.): Bronzezeit in Ungarn. Forschungen in Tell-Siedlungen an Donau und Theiss. Frankfurt am Main, 153–155.

Sorensen, M.L.S.–Rebay-Salisbury, K. 2008. Landscapes of the body: burials of the Middle Bronze Age in Hungary. European Journal of Archaeology 11 (2008) 49–74.

Schreiber R. 1984. Szimbolikus ábrázolások korabronzkori edényeken – Symbolische Darstellungen an frühbronzezeitlichen Gefäßen. Archaeologiai Értesítő 111 (1984) 3–28.

Vicze, M. 2009. Nagyrév symbolism revisited: Three decorated vessels from Százhalombatta and Dunaújváros. Tisicum. A Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Megyei Múzeumok Évkönyve 19 (2009) 309–318.