New tools in humanities: bioarchaeology and biosocial archaeology

What kind of science is modern archeology?

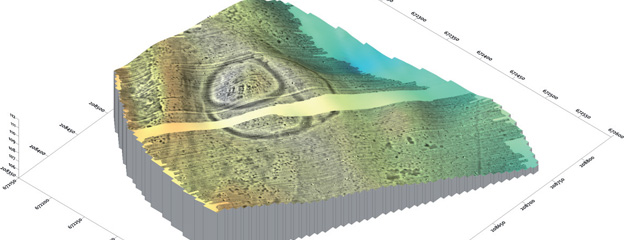

In Central Europe, it is traditionally part of the historical sciences, sometimes considered an auxiliary science of the latter. At the same time, major part of its methods are taken from natural sciences, primarily geology. In addition, results of many natural sciences are integrated, as research fellows of the Institute of Archeology has already reported in several studies. Radiocarbon dating, the analysis of former diet or migrations, isotope geochemistry and archaeogenetics, the increasingly successful use of geophysics to locate settlements and graves, and the application of the ever-refining methods of palaeopathology in archeology provide much information. Archaeologists just need to fit the parts of the mosaic together, don’t they?

The question is also relevant for the Momentum Mobility research group of the Institute of Archeology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, where we analyze Bronze Age transformations interdisciplinarily. While Bronze Age is usually associated with Mycenaean and Trojan heroes, our research group investigates slightly older periods: the history of the first thousand years of the Hungarian Bronze Age (between 2500 and 1500 BC).

We examine communities (e.g. Bell Beaker culture, Tumulus grave culture) which – based on traditional archaeological analysis of burial customs, changes in settlement structure, or elements of material culture – were related to smaller or larger migration waves and the appearance of “foreign” groups in present-day Hungary. In addition to population genetic events suggesting human mobility, we also attempt to discover kinship relations and the structure of society. The examination of settlements, residential houses, and bronze objects provides an insight into the arenas of everyday life and the hierarchical relationship between small and large villages.

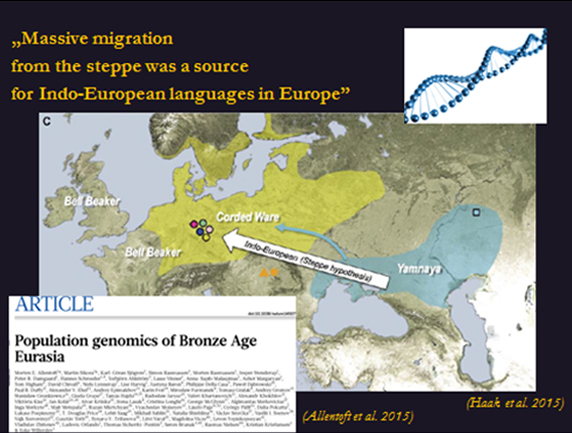

As we can see today, migration is a very important social strategy, which people often use to solve their problems and improve their status. Our research is supported by a new, complex discipline: bioarchaeology. Supported by detailed biological and archaeological analysis of human remains, it becomes possible to draw the history of smaller communities and individuals. Our research group is involved in a genomic project launched by the Institute of Archeology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and Harvard Medical School, which can prove eastern and western population movements affecting the territory of Hungary. With the help of the results we participate to answer pan-European research questions such as the migration of Indo-European peoples – as shown by two studies, co-authored in Nature last year by members of our research group (Allentoft et al. 2015, Haak et al. 2015).

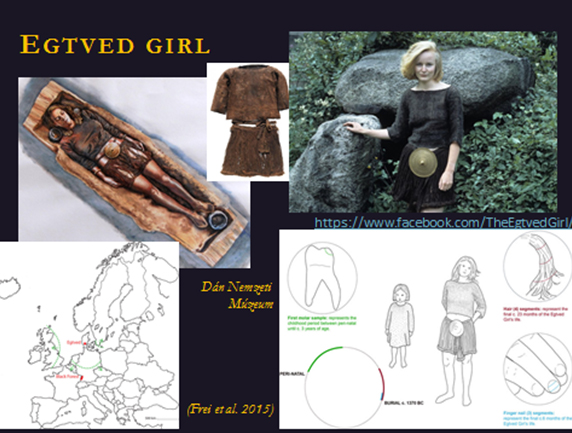

A good example for the effectiveness of bioarcheology is the research of the well-known young woman, the “Egtved Girl”, buried between 1500 and 1300 BC. An interesting feature of the burial found in the southern part of the Danish Jutland peninsula in 1921 was that the acidic medium provided by the oak coffin preserved the entire clothing of the 16-18-year-old girl and parts of her body in an unusual way. The woman buried in a cord skirt, equipped with a ‘sundisc’ belt is one of the emblems of the Bronze Age. In 2011 a Facebook page was created for her in connection with a research project of the National Museum of Denmark. A study based on the girl’s teeth, manicured nails, and blond hair, published in Nature in 2015, found that the young woman was born outside Denmark, as results of strontium isotope analysis of her first molar grown in infancy differ from the strontium isotope ratio of her burial place. The raw material of her wool clothes and blankets, and the cowhide under her body, do not originate from present-day Denmark. Based on these stable isotope data and the bronze dagger found in her burial, the young girl was originated from the region of the Black Forest in southwestern Germany. According to Danish researchers, she traveled a lot in the last two years of her life, probably supporting the relations between the communities of the two regions by a diplomatic marriage.

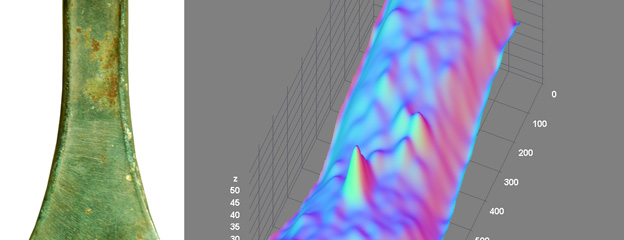

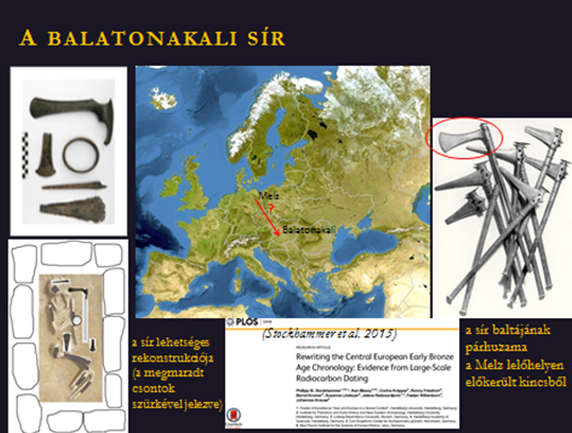

We are looking for answers to similar questions (time period, health conditions, production place of grave goods) during the analysis of Bronze Age burials in Hungary, e.g. the high-status man found in the 1960s in the vicinity of Balatonakali. Unfortunately, this grave was not discovered by archaeologists, but during construction works; however a remarkably large number of bronze tools and weapons, as well as a golden hair ring suggested a prestigious burial (Torma 1978). The extremely fragmentary bones (remaining pieces of the skeleton marked in gray on the picture), however, have been preserved in the Dezső Laczkó Museum in Veszprém, and we have the possibility to establish new results based on the examination of the remains. According to anthropological analysis, a man between the ages of 55 and 60 lay in the grave. We attempt to reconstruct the original position of the skeleton and grave furniture using the description of the find circumstances and the green patina on the bones caused by the corrosion of the bronze objects.

In cooperation with the Centre for Energy Research and the Wigner Physics Research Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, we analyze the metal objects. The raw material of the axe, which has connections to northern Germany in terms of its shape, differs from the material of the other objects from the burial, which confirms the earlier assumption that it may have become the property of the man as a result of long-distance exchange. A more precise indication of the origin of the raw material is expected from the lead isotope analysis to be performed at the CEZA laboratory in Mannheim. The ongoing ancient DNA and stable isotope study can reveal whether the elderly man was born in the Balaton region or came to western Hungary from a remote place. According to the radiocarbon dating, made by the Hertelendi Laboratory of Environmental Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the man was laid to rest around 1950-1900 BC. In collaboration with the Debrecen laboratory, the project will produce formerly lacking AMS radiocarbon dates from the Bronze Age of the Carpathian Basin, contributing to recently published absolute chronological research of the same period in Central Europe (Stockhammer et al. 2015).

In the second part of the lecture, we show how the biosocial analysis can be continued through the example of a special group of findings. During the Bronze Age, we encounter many burial customs, from inhumations to cremation and rich, stone-chambered mounds. However, it seems to be more and more common that we find human remains outside the “traditional” cemeteries in both the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, especially in settlement pits. Who could these people have been and why couldn’t they rest in cemeteries? Could they be strangers, perhaps for some reason outcasts? Or the answer isn’t that simple and we are dealing with something completely different?

In addition to traditional archaeological methods, a number of other studies are required to interpret these special findings. Among these, for example we can mention the soil micromorphological analysis, in which thin-sections taken from soil samples are examined under a microscope. This method can be used to determine, whether a given pit was open after the corpses were placed in (indicated by rain-washed, wind-borne microlayers) or the mixed bones were excavated from elsewhere and re-buried with soil from the original burial place. The stable isotope, aDNA, radiocarbon analyzes already mentioned above, which can be performed on both human remains and companion samples, can also be useful.

Data from various studies are included in a system during interpretation. Our goal is to look for potentially repetitive patterns in the archaeological material (e.g., age, gender, and context, possibly associated with grave goods). The gradually expanding database and the increasingly ordered pieces of information eventually form a unit from which we can even draw cognitive archaeological conclusions.

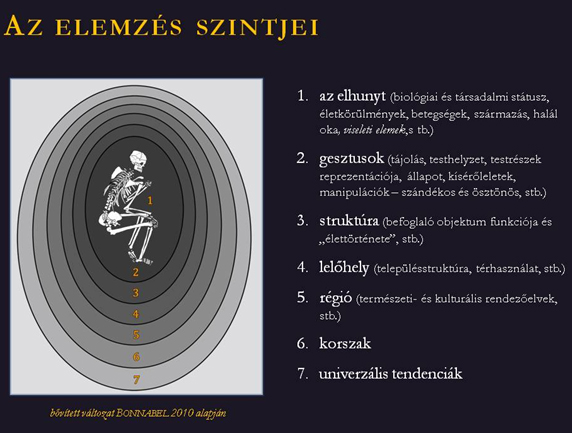

In each case, the analysis is started at the level of the smallest unit, i.e. the deceased. We examine the physical anthropological data on the individual’s identity, social status, living conditions, and possibly the cause of death (whether there is gender and age discrimination, traces of injury, deficiency diseases or other characteristics), as well as the costume elements of the deceased. The results obtained are also compared with the characteristics observed in “classical” cemeteries. In the case of the Late Bronze Age finds, for example, it turned out that in addition to the dead in the pits of the settlements, only the elements of the simplest, ordinary wear were found, or that women and children were often turned to their sides, while men were mostly laid in one of the four main equator. As a next step, we analyze any archaeological traces that suggests preburial treatment of the corpse/human remains. The orientation of the dead, the method of laying them, the condition of human remains, the presence of body parts, traces of manipulations before and after death all equally contribute to the reconstruction of the sequence of events related to the disposal of human remains. We also examine whether the object containing the human remains was dug specifically for the deposition, or whether an existing pit was used for disposal. Based on the location of the remains it can usually be concluded that someone along with the corpse descended into the object and carefully guided it there, possibly that the remains were wrapped in something or simply thrown into the pit.

It was revealed that human remains during the period between 1300 and 800 BC were almost always placed in abandoned storage pits and buried with soil that also contained household waste. Before the disposal of the corpses, some kind of burning activity was carried out many times, traces of which (ash layers, burnt objects or bones) can also be found in the objects. Many times there was a grinding stone and deliberately fragmented ceramic vessel next to the dead – both of which may have had a strong symbolic meaning. After all this, we examine exactly where the objects containing human remains were located within the site. In a broader sense, this requires the definition of activity zones and horizontal stratification of the site.

We also analyze micro-regional and regional differences, which again requires multidisciplinary research. In a database, we summarize the sites of the sample area that can be classified into a given period, examining also the location of the burial sites and the place of human remains occurring within the settlement in the settlement network. Overlapping levels of analysis result in a knowledge of a gradually expanding, broader context. By micro-level comparative examination of the various factors, we can first arrive at the reconstruction of the deposit process, and by comparing the individual cases, we can arrive at a more universal interpretation of the phenomenon. If the results allow, by the end of the whole research series it will be possible to map the former sociocultural/cognitive drivers, and perhaps we can answer the question whether the disposal of the bodies within the settlement is part of the “traditional” burial rite, whether it is connected or is completely independent of it.

From all this we can see that bioarchaeology gives us an outstanding group of sources in terms of the way of life of the contemporary man, which we can also exploit with the help of the Momentum Program. We can answer the question outlined in the introduction, that the task of an archaeologist does not end with the discovery of scientific results, but that it begins, since the ultimate goal of archeology is to understand man as a social being.

Viktória Kiss – Ágnes Király

The presentation was held on 17 November 2016 at the scientific meeting day “The Momentum Program in the Humanities“.

References:

Allentoft, M.E., Sikora, M., Sjögren, K.G., Rasmussen, S., Rasmussen, M., Stenderup, J., Damgaard, P.B., Schroeder, H., Ahlström, T., Vinner, L., Malaspinas, A.S., Margaryan, A., Higham, T., Chivall, D., Lynnerup, N., Harvig, L., Baron, J., Della Casa, P., Dąbrowski, P., Duffy, P.R., Ebel, A.V., Epimakhov, A., Frei, K., Furmanek, M., Gralak, T., Gromov, A., Gronkiewicz, S., Grupe, G., Hajdu, T., Jarysz, R., Khartanovich, V., Khokhlov, A., Kiss, V., Kolář, J., Kriiska, A., Lasak, I., Longhi, C., McGlynn, G., Merkevicius, A., Merkyte, I., Metspalu, M., Mkrtchyan, R., Moiseyev, V., Paja, L., Pálfi, G., Pokutta, D., Pospieszny, Ł., Price, T.D., Saag, L., Sablin, M., Shishlina, N., Smrčka, V., Soenov, V.I., Szeverényi, V., Tóth, G., Trifanova, S.V., Varul, L., Vicze, M., Yepiskoposyan, L., Zhitenev, V., Orlando, L. Sicheritz-Pontén, T., Brunak, S., Nielsen, R., Kristiansen, K., Willerslev, E.: Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522 (2015) 167-172.

Bánffy E.: Mi az idő? Titok. A mai magyar régészeti kutatás helyzetéről. Magyar Tudomány 2004/11, 1240–1245.

Frei, K. M., Mannering, U., Kristiansen, K. Allentoft, M. E., Wilson, A. S., Skals, I., Tridico, S., Nosch, M. L., Willerslev, E., Clarke, L., Frei, R.: Tracing the dynamic life story of a Bronze Age Female. Nature Scientific Reports 5 (2015), Article number: 10431

Haak, W., Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Llamas, B., Brandt, G., Nordenfelt, S., Harney, E., Stewardson, K., Fu, Q., Mittnik, A., Bánffy, E., Economou, C., Francken, M., Friederich, S., Pena, R. G., Hallgren, F., Khartanovich, V., Khokhlov, A., Kunst, M., Kuznetsov, P., Meller, H., Mochalov, O., Moiseyev, V., Nicklisch, N., Pichler, S.L., Risch, R., Rojo Guerra, M.A., Roth, C., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Wahl, J., Meyer, M., Krause, J., Brown, D., Anthony, D., Cooper, A., Alt, K.W., Reich, D.: Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522 (2015) 207–211.

http://humanities.ku.dk/news/2015/the_bronze_age_egtved_girl_was_not_danish/

Stockhammer, P. W., Massy, K., Knipper, C., Friedrich, R., Kromer, B., Lindauer, S., Radosavljevic, J., Wittenborn, F., Krause J.: Rewriting the Central European Early Bronze Age Chronology: Evidence from Large-Scale Radiocarbon Dating. PloS One 10 (2015): e0139705

Torma, I.: A balatonakali bronzkori sír (Das bronzezeitliche Grab in Balatonakali). Veszprém Megyei Múzeumok Közleményei 13 (1978) 15–24.

Weiss-Krejci, E.: The Formation of Mortuary Deposits. Implications for Understanding Mortuary Behaviors of Past Populations. In: S. C. Agarwal/B. A. Glencross (eds.), Social Bioarchaeology (Chichester 2011) 68–106.